INTRODUCTION

As with so many things I write about, I was moved to undertake this research by the acquisition of some VERY expensive photographs back at the beginning of 2012. Little did I know what would be involved and how exciting the outcome would be. Here is my chance to share it with you.

The first step was to consult Timothy J McCann, historian, former West Sussex Assistant County Archivist and current Chairman of the Heron-Allen Society. I was trying to identify people in the photographs and had run into a brick wall. Before you could say ‘Jack Robinson’ we were talking to a huge variety of experts as you will see from the Acknowledgements at the end of the article. It was tantalising to discover that the bones of the mammoth had been on a shelf in the Natural History Museum since June 1909 and that no new investigations had taken place. With the advances in forensic science it was decided that funding would be sought and our mammoth subjected to modern research methods. And so it was.

I decided that while I couldn’t participate in this activity, I could certainly research the press reports and the people and, for the past three years, this has been a huge part of my life. I hope you find the results interesting.

THE STORY IN THE PRESS

The first intimation that anything was afoot in Selsey was an article which appeared in the West Sussex Gazette on Thursday, 18 March 1909.

‘SELSEY, LEVIATHON ON THE BEACH

An interesting discovery is reported from Selsey. On Tuesday, James Lawrence, a fisherman, found on the beach, opposite Mr H A Smith’s bungalow, and some 25 feet below low water mark, a mass of red clay in which were embedded the remains of what appears to be a mammoth. The bones seem to be those of an animal 30 feet in length, and some that have been removed weigh in all between ten and twelve cwt. Two great teeth have been brought to our office in Chichester, where they may now be seen. We are at present at a period of neap tides; it is hoped that during the spring tides of next week it will be possible to make a more careful examination of the remains. It is supposed that the easterly wind which has been prevalent for weeks has had much to do with causing the mass of clay to move and become uncovered.’

This was picked up by the Sussex Daily News of the same date.

‘MAMMOTH IN THE CLAY

Important Selsey discovery

A discovery of considerable interest and importance was made at Selsey on Tuesday by James Lawrence, a fisherman, of North Road. At low tide he found opposite to Mr H A Smith’s bungalow, embedded in a mass of red clay, the remains of what was undoubtedly a mammoth, measuring about 30 feet in length. Some of the bones, weighing several hundred-weight, and also four teeth, were removed. Two of the teeth, which had the appearance of great lumps of iron, and were nearly as heavy, were taken to Chichester yesterday, and were the subject of curiosity by many to whom they were shown. In the course of an interview on the discovery, Mr Smith expressed the opinion that the recent easterly winds were the cause of the clay being removed and the remains becoming exposed, and it is hoped that in the course of the next few days the spring tides will enable a closer inspection of the remains to be made.’ And also by the London Evening News that same evening although with much more restrained coverage

SELSEY MAMMOTH

The remains of a mammoth – the bones covering a tract of 30ft – have been found at Selsey, Sussex, by a local fisherman named Lawrence.

They were embedded in a patch of red sand on the seashore.

The ‘Tuesday’ referred to was 16 March and Mr Henry Arnell Smith, aka ‘Darkie’ or ‘HA’, lived in ‘The Hut’ which was completely destroyed on 6 March 1912 due to severe gales.

So almost immediately, Selsey became the centre of attention countrywide.

By 23 March, when the Daily Graphic made its own report and by which time the ‘dig’ had been commenced (on 20 March), the focus had shifted to the scientific aspects of the beast and so we find that Dr A Smith-Woodward, Keeper of Geology in the British Museum, Edward Heron-Allen (which of course was inevitable) and Henry Arnell Smith directing the dig. The Graphic reported that it was a complete skeleton and that the bones were scattered, broken and water-worn. Edward Heron-Allen took the opportunity to take sediment samples.

The Globe of the same date borrowed heavily from the Graphic report but we must credit The Chichester Observer of 24 March with by far the most comprehensive report to date.

‘THE SELSEY MAMMOTH

HUGE BONES DISCOVERED IN CLAY

EXPERT EXAMINATION OF THE SKELETON

Selsey has once again come prominently before the British public, not, this time, through the gallantry of its fishermen, but on account of the discovery of Palaeolithic remains of considerable interest and importance. The remains are those of a mammoth, a huge animal of the elephant variety which lived thousands of years ago. The discovery was made by James Lawrence, a fisherman, of North Road, Selsey, whose attention was attracted by a portion of bone of huge dimensions and weight. They were found, after the recent easterly winds, at low tide embedded in a mass of clay, immediately opposite Mr H A Smith’s bungalow, ‘The Hut,’ about sixty-six feet from the sea bank.

Although only about twenty or thirty portions of bones have been discovered to the present there is no doubt that further excavations will be made when the tides permit, and some idea of the size of the animal may be gained from the fact that the tract over which the bones appear to spread measures about thirty feet.

As soon as the news of the discovery was made known, Mr H A Smith received a letter from Dr A Smith Woodward, Keeper of Geology in the British Museum, intimating that if the skeleton proved to be a good one the authorities of the British Museum would undertake its removal. Hence he advised that its removal should not be undertaken by inexperienced diggers, who might destroy it.

Following this, Dr Woodward himself paid a visit to Selsey, and on Saturday conducted an examination of the remains. With him were Professor Gregory, of Appledram, and Mr E Heron-Allen, of Selsey. The remains were found below high water mark in a fresh water deposit of black clay, which is usually covered with a thick bank of shingle. The bed has not been exposed before within the memory of the present generation of fishermen, and is rapidly disappearing again. Extensive diggings, under the direction of Mr E Heron-Allen and Mr H A Smith, have now shown that although a large part of the skeleton must have been originally present, the bones are scattered and broken, and in many cases, water-worn. The molar teeth of both jaws are well-preserved, and indicate that the animal was an ordinary mammoth, not fully grown. Dr Woodward thought that the skeleton may have been exposed some years ago, and portions of it washed away by the sea, but the form of the complete carcase is quite distinct. Owing to the spring tides, further operations will doubtless have to be postponed for a fortnight.

The bones already removed have been deposited in Mr H A Smith’s bungalow, where an ‘Observer’ representative had an opportunity of seeing them. The bones, which resemble lumps of iron in appearance and weight, include hip and short ribs, knee caps, ankle bones, and four teeth. The knee caps, both in size and weight, are like the half of a cannon ball, while the teeth, which weigh from 6-lbs to 8-lbs each, are about the size of a 3-lb jam jar.

Dr Woodward expressed the opinion that the animal in all probability died where it was found, and in conversation with Mr H A Smith, said that it was quite likely that the remains were 4,000 years old’.

As we shall see, the estimate of its age is wildly inaccurate and so was the phrase ‘an ordinary mammoth’ but this may be excused as the Victorians and Edwardians thought there was only one type of mammoth and a later conversation reported in the Worthing Evening News indicated that they knew nothing of the ages attained by mammoths.

The report from the Worthing Evening News was reproduced, in part, by the West Sussex Gazette of 25 March but it did enable us to add another person to the list of the great and the good who continued to visit, that of the Reverend J Cavis- Brown. John Cavis-Brown was Selsey’s vicar at the time and was, himself, an ardent historian so well respected that Heron-Allen went to some trouble to rescue the late vicar’s historical research from a bonfire which assisted greatly in the production of Selsey Bill 1911.

The magazine Nature published one report on 25 March and another on 22 April. The earlier report mirrors much of what went before but the later one mentions another distinguished person, Dr Clement Reid FRS of whom we will learn more later in the article.

The Sphere of 27 March published the first picture of the bones, labelling them ‘The Remains of a Mammoth found on the Beach at Selsey Bill’. They are pictured outside Henry Arnell-Smith’s home on a small gate-leg table, presumably belonging to HA.

If the great and the good couldn’t get to Selsey, then they wrote to Heron-Allen, the path followed by the Rev. James Conway Walter on 15 April 1909. Here was yet another vicar with an interest in history, one of his publications being entitled the ‘History of Horncastle’ where Langton Rectory was his home. The first page of his letter is reproduced by kind permission of West Sussex Record Office, ref. MP110, and is to be found in Heron-Allen’s Selseyana.

As it took me many a long hour to decipher this learned gentleman’s handwriting, I am including a transcription:

‘My dear Sir

I am much interested in the discovery of remains of a mammoth at Selsey Bill, a part of the Sussex Coast on which I have had many a ramble – with gun and without – in former years.

At my request, my friend Mr Arthur Ingleby, now of Worthing, called upon you to get what information he could about the said remains. It seems a great pity that the whole are not being carefully taken care of.

I have before me, on my table, as I write, in my study, a mammoth tooth, found near here in the gravel of an old Celtic stream, the Bain river (‘Bain’ meaning ‘bright’), and the British Museum has one curious geological object which I found, besides having given me information about another antique, in my possession, which goes, coming year to Church Congress, by request, for exhibition.

Could not this mammoth be preserved and sent to the British Museum? A letter to the Secretary of the Geological Department, would probably get this managed. Could you kindly give me particulars to the actual remains found, whether in the clay, or what, the length of the whole, etc,. etc?

I am Hon Member of the ‘Spalding Gentlemen’s Society’, the oldest provincial, antiquarian society in England, founded by the founders of (the) Society of Antiquarians, London and I might read a paper on the subject.

I may say, I have written the Histories of about 70 parishes in this neighbourhood, having recently completed that of our old Roman and British Town of Horncastle.

I used to know Sussex as well as I know this County: have walked most of the County, from Brighton to Guildford in Surrey and from beyond Chichester, to Hastings, Winchelsea, Fairlight, etc.

I am, yours faithfully,

J Conway Walter

I enclose extract which, if you reply, please return. I formerly belonged to the Brighton Naturalist’s Society and have a Roman lamp found near a village, Clapham, inland on the Downs, above Worthing.’

James Conway Walter died on 19 March 1913. I wonder if he ever knew that Edward Heron-Allen did, indeed, send the bones, in two champagne boxes, to the British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London on 4 June 1909.

Also in Selseyana is a letter from Dr. A Smith Woodward dated 7 June, sent from British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW, and posted at 8pm on the same day:

‘Dear Mr Heron-Allen

With very many thanks, I have safely received the two boxes of bones and teeth of the Selsey mammoth; and you will receive an acknowledgement of your kind present after the next meeting of the trustees. We shall be pleased to arrange for a photograph at any time.

Yours sincerely

A Smith Woodward’

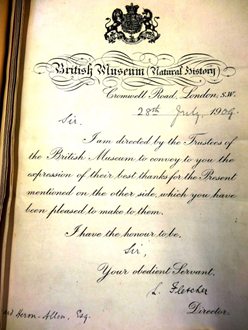

In due course, on 28 July, a formal thank you was sent by A Fletcher, Director of the British Museum with an attachment identifying what was sent, viz.- ‘4 molar teeth and associated bones of a young Mammoth (Elephas primigenius), from the beach at the fishing village of Selsey, Sussex.’

‘Sir,

I am directed by the Trustees of the British Museum to convey to you the expression of their best thanks for the Present mentioned on the other side which you have been pleased to make to them.

I have the honour to be, Sir,

Your obedient Servant,

L Fletcher’

A small digression is necessary at this point as we take issue with the word ‘Present’. The letter is obviously a ‘standard’ letter with the appropriate appellations added.

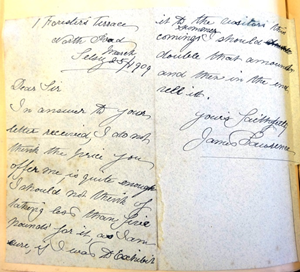

On 25 March 1909, writing from his home at 1 Forester’s Terrace, North Road, Selsey, James Lawrence addressed Heron-Allen thus:

‘Dear Sir

In answer to your letter received, I do not think the price you offer me is quite enough. I should not think of taking less than five pounds for it, as I am sure, if I was to exhibit it to the visitors this coming summer I should double that amount and then in the end sell it.

Yours faithfully

James Lawrence’

Dr Smith Woodward wrote a somewhat testy letter to Heron-Allen on 29 March on behalf of the British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London, S.W:

‘Dear Mr Heron-Allen,

We thank you very much and shall be pleased to see you on Wednesday afternoon or whenever you can call.

Five pounds is an extreme price for the mammoth remains, including the 4 molars; but I think, if we were buying them, I should advise the Trustees to rise to that amount.

Yours Sincerely,’

If only he knew then what we know now, perhaps he would have changed his view.

But it wasn’t only in the UK that our mammoth made news. There are reports of it in the ‘Grey River Argus’ of 19 May, page 4 and ‘The Colonist’ Vol. L1, issue 12573 of 24 June 1909, page 1, both of these being published in New Zealand. ‘The Straits Times’ of 28 September 1909, page 5, published in Singapore, also carried the news.

Truly a worldwide phenomenon.

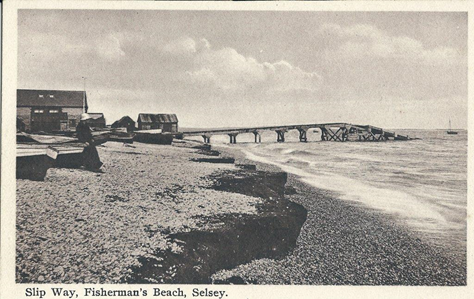

THE MAMMOTH SITE

But where was this remarkable animal found? ‘On the beach, opposite HA’s bungalow’ was only helpful in 1909 but ‘The Hut’ blew away. The West Sussex Gazette reported that the site was ‘25 feet from low water mark’ and The Chichester Observer records that it was ‘65 feet from the sea bank’. However, Edward Heron-Allen defined the spot in his own notes ‘132 feet from brow of the shingle at right angles to the high-water mark, due SE from the S boundary of HA’s bungalow’.

As we all know, coastal erosion diminishes the usefulness of even this data but greater minds than I have determined that this postcard shows the site. The postcard is undated but it can be no earlier than 1902 which is when the split-back first appeared on postcards (separating message from address) and no later than 1920, when the second lifeboat house was built. Simon A Parfitt, of the Natural History Museum, states in his report, which appears in Opusculum XX of the Heron-Allen Society, that:

‘At the actual site the beach was located at the end of the ‘slip way’…; it would now lie some 200 metres seaward from the existing sea wall and about 270 metres north of the current (2014) Lifeboat House.’

And here is Henry Arnell Smith on the left and James Lawrence on the right ‘digging’ for mammoth bones.

Here are our two heroes again, this time holding mammoth teeth, in front of ‘The Hut’, a converted railway carriage with a ‘Smoking’ sign etched onto the window and providing the photographer’s reflection.

Observant readers will notice that the colour and consistency of the medium in which the skeleton was discovered changes from red clay to red sand to black clay in the newspapers. Again, Heron-Allen provides the definitive answer in Selsey Bill, Historic and Prehistoric, 1911, page 54:

‘A black and brown fresh-water clay, containing Pleistocene wood and roots, and seeds of fluviatile plants’.

His samples, which still exist, are labelled ‘Brown bands in black sandy clay from which the mammoth bones were taken’.

Samples of the clay were sent to Dr Clement Reid who, on 27 March 1909, wrote to Heron-Allen with his findings:

‘7 St James’ Mansions, West End Lane, N.W.

Dear Mr Heron-Allen

Mrs Reid and I have examined the sample of clayey sand found with the Selsey Mammoth; it is full of seeds belonging to at least 8 species, so it is well worth further study. If you care to wash a quantity and let us have the seeds (wet) we shall be glad to determine them for you.

The material is quite easy to wash and does not require drying or boiling.

Yours faithfully,

Clement Reid’ ‘Mrs Reid’ is Eleanor Mary Wynne Edwards whom he married in St Asaph in 1897.

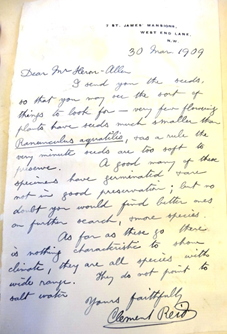

On 30 March Clement Reid wrote again:

Dear Mr Heron-Allen,

I send you the seeds, so that you may see the sort of things to look for – very few flowering plants have seeds much smaller than Ranunculus aquatilis and as a rule the very minute seeds are too soft to preserve. A good many of the specimens have germinated and are not in good preservation; but no doubt you would find better ones on further search, and more species.

As far as these go there is nothing characteristic to show climate, they are all species with wide range. They do not point to salt water.

Yours faithfully’

We have Heron-Allen’s notes in Selsey Bill, Historic and Prehistoric 1911so we can say, with confidence, that cinquefoil, water milfoil, spike rush, water crowsfoot, horned pond weed, two species of sedge, pond weed, stitchwort and mares’ tail were found, all plants which thrive in fresh water. He does, of course, also include the Latin names in the above publication (page 55) as is plate VIII depicting some of the mammoth bones, facing page 64. He also draws the conclusion that the mammoth died ‘by the side of a river or an inland lake’.

(© Ivor Jones)

Simon Parfitt draws a pen picture of a low-lying landscape with a slow-flowing river network including pools, lakes and marsh with drier ground supporting woodland of pine and birch and grassland. In short, it was a pleasant place to be despite the temperature probably being lower than today.

DEM BONES, DEM BONES, DEM (NOT SO) DRY BONES

The press reported Dr Smith Woodward’s concerns that some of the skeleton had been washed away in previous storms and that inexperienced diggers might destroy it. The fact that not all of the bones in the photographs reached the Museum is hardly surprising as we read that the dig was undertaken in between tides and constant gales were throwing more shingle on top of the site. There are however, several other factors to take into account. The main participants may have kept a bone or two, museum curators may have discarded some in the mistaken belief that they were uninformative while Heron-Allen makes it clear on page 54 of Selsey Bill, Historic and Prehistoric, 1911, that:

‘Unfortunately, the bed in which the bones were found was only exposed for a few days, and then only for about three-quarters of an hour at a time, and an impression having got abroad that money might be obtainable for any fragment of the skeleton, the moment the bed was exposed a seething mass of inhabitants, armed with every conceivable digging implement attacked it and the skeleton which might have been a most valuable ‘find’ had the inhabitants consented to allow it to be dug out systematically by experts, was brought up in small fragments by anyone who could seize hold of a piece, being in an extremely soft and friable condition.’ (© Ivor Jones)

On 5 April 1911, the Chichester Observer reported that ‘While trawling off Selsey last week, a fisherman named Tadd brought up a mammoth’s tooth weighing nearly 6lbs. Mr Tadd has the tooth at home for the inspection of anyone interested. It will be remembered that some remains, supposed to be those of a mammoth, were discovered below high water mark two years ago’.

In the 1960’s an ‘elephant’ shoulder blade was found loose on the seabed by a diver spear-fishing less than a hundred metres from the 1909 find-spot (Parfitt, Op. XX).

Do you have any unidentified bits of ‘elephant’ at home?

However enough of the animal survived to allow meaningful conclusions to be drawn. The teeth of the Selsey Mammoth indicate that it was about 30 years old and while one cannot define the sex of the animal due to the absence of the pelvis, the probability is that it is male and stood 9 feet (2.7 m) at the shoulder. (Parfitt, Op. XX).

So why are we all so excited? After all, there was a Selsey Mammoth in 1859, found around Danner, and another in the 1960’s.

I just happen to have a mammoth tooth in my possession, photographs of which have been sent to the Natural History Museum. Their verdict is that it is a woolly mammoth based on, among other things, the spacing of the plates on the teeth. If we look closely at this mammoth’s teeth, we see that the plates on the modern coloured picture are quite close together while the black and white picture of the 1909 mammoth shows rather widely-spaced plates.

So if it’s not a woolly mammoth, what is the 1909 Selsey Mammoth? Put, quite simply,

IT’S A WORLD FIRST!

As Simon Parfitt says in Opusculum XX, ‘Unbeknown to Heron-Allen and his associates, they had discovered the first skeleton of steppe mammoth to have undergone scientific scrutiny.’

‘Now, more than a century after its discovery, the true significance of the Selsey mammoth is apparent. A re-assessment of the few surviving bones and teeth suggests that it was a late form of the steppe mammoth lineage; a find of great significance given that less than a dozen complete or largely complete skeletons referable to this species are known to date. These span a vast geographical area, from West Runton in Norfolk to north-eastern Kazakhstan (Russia), and more than half a million years in time (Lister & Stuart, 2010, Table 1). The skeleton from Steinheim (Germany), found in 1910, is generally credited with being the first steppe mammoth skeleton to be discovered. This distinction now must lie with the Selsey Mammoth, which was found the previous year.’

AN ORDINARY MAMMOTH? Most definitely not! It is a late steppe mammoth, existing alongside its woolly successor in the middle to late Pleistocene era. It roamed the earth probably between 243,000 and 191,000 years ago – a far cry from the 4,000 years we saw reported.

SO WHAT HAPPENED NEXT?

Just when I thought we had found out everything there was to find, I received an email from David Bone attaching this. The journal was that of the ‘British Empire Naturalists’ Association (now called the ‘British Naturalists’ Association) which is now called simply Country-Side.

He had acquired a copy of EH-A’s famous Selsey Bill tome and found it tucked inside. For those interested in minutiae, John Carreck looked after the archive photograph albums of The Geologists Association and I am grateful to David for telling me. This is the only publication we have come across which attributes the photographs to W E Carter. Frantic Googling revealed nothing on this gentleman; however, it did reveal the website for Sussex PhotoHistory and, on the grounds of nothing ventured, nothing gained, I contacted David Simkin who was not only able to tell me that W E Carter was an amateur photographer from Worthing but also included his potted history and the information that W E Carter was a member of Worthing Camera Club.

As you are reading this it is the 3rd anniversary of the photographs being bought and the 106th anniversary of the mammoth discovery. A very suitable coincidence!

So here we have the story of the photographs, the finding of the mammoth and its own story. But what of the people involved?

Ruth Mariner 2015

Acknowledgements

Ivor Jones who has allowed me to quote from Selsey Bill, Historic and Prehistoric, 1911 by Edward Heron-Allen.

Timothy J McCann for his support, encouragement, and enthusiasm. Copies of Opusculum XX may be acquired from him for £10 from: Timothy J McCann, Chairman of the Heron-Allen Society, 18 Oaklands Road, Havant, Hants, PO9 2RN.

John E Whittaker of the Heron-Allen Society for being so generous with his time and knowledge.

Simon Parfitt of the Natural History Museum who devoted his time and energy to acquiring the funding for and undertaking the first full scientific research of the 1909 Selsey Mammoth.

David Bone, Geologist and Fossil Hunter and member of the Heron-Allen Society for his contribution to the story and for his ongoing support on other matters.

David Simkin of Sussex PhotoHistory, www.photohistory-sussex.co.uk who stepped outside his usual role to provide me with information on W E Carter.

Michael Demidecki, Editor of Country-Side, www.bna-naturalists.org. for allowing me to reproduce his journal.

Trish Greenwood of Selsey who assisted me by positively identifying which James Lawrence I needed to research.

Brenda Joyce of New Zealand, relative of Henry Arnell-Smith who identified the people in the photograph of HA’s family.

Carol Marshall of who put me in touch with

Dorothy Morgan, grand-daughter of W E Carter, who has been supporting me in my quest

Kathy Codling who is related to the Hunnisett family and confirmed Harry’s identity.

And finally,

The Staff of West Sussex Record Office who, as usual, gave me all the assistance I requested.